Sixty years after the gunshots of January 15, 1966 shattered Nigeria’s First Republic, Major-General Ibrahim Bata Malgwi Haruna (rtd) speaks with the unsettling calm of a man who has seen the nation before it broke—and after it refused to heal.

In an expansive, often explosive conversation with Vanguard, the former Federal Commissioner for Information and Culture and past Chairman of the Arewa Consultative Forum does not offer nostalgia. Instead, he offers something more dangerous: memory sharpened by history, and conclusions that refuse to flatter any region, generation or foreign power.

For Haruna, the coup led by Major Chukwuma Kaduna Nzeogwu was not an accident, not an aberration, and certainly not the singular tragedy many narratives have reduced it to. It was, in his words, “almost inevitable.”

A Nation Born Unequal

Haruna’s recollection slices through sentimentality. Independence in 1960, he argues, was partial and poorly structured. Nigeria emerged not as a settled federation but as an awkward hybrid—“between a confederation and a federation”—with regions unequal in size, population, resources and power.

The North towered demographically and territorially. The East and West bristled with economic ambition and political anxiety. Lagos sat awkwardly at the centre. What followed was not nation-building but competition—ethnic, regional, religious.

Politics hardened into tribal warfare by other means. Christian versus Muslim. Majority versus minority. Region versus region. Even the instruments of order—the police and the military—were caught in rivalry, each jostling for relevance in a fragile state where authority itself was contested.

By the mid-1960s, the ground was already soaked in tension. The coup merely lit the match.

Soldiers Who Thought They Could Do Better

Inside the military, Haruna recalls, young officers—many trained abroad, many commissioned just before or after independence—absorbed the bitterness of civilian politics. They watched corruption, abuse of power and ethnic manoeuvring and concluded, dangerously, that they could do better.

The irony is brutal. The same problems the coup claimed to end—tribalism, corruption, imbalance—became its most enduring legacies.

Haruna knew the coup plotters personally. He was their contemporary, a major like them, commanding the Ordnance Depot in Yaba. Kaduna Nzeogwu, he says, was only slightly senior. Others, like Anuforo, were part of the same generational cohort—officers shaped by independence, ambition and a belief that force could fix what politics had broken.

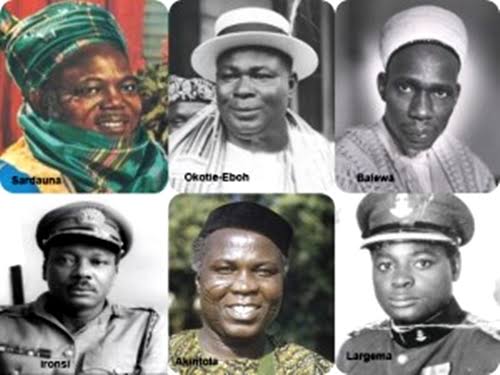

The perception that the coup favoured one region, and punished others unevenly, detonated the nation’s fault lines. The political killings were not just deaths; they were symbols. And symbols, in Nigeria, have consequences.

Did the Coup Destroy Nigeria’s Future?

Haruna is unsentimental about a popular claim: that Nigeria’s development was set back irreparably by the 1966 coup.

“Nigeria was not progressing anyway,” he says bluntly.

Ethnic unions had already hardened. The Igbo State Union, the Action Group, the politics that stopped Nnamdi Azikiwe from becoming Western Region premier—these were signs of a country already retreating into identity. Aburi, the Civil War, successive national conferences and decades of military rule were not deviations, Haruna suggests, but continuations of unresolved arguments.

In that sense, Nigeria today—with its flawed democracy, restless regions and recurring insecurity—is still negotiating the same questions, just without tanks on the streets.

Why the North-South Divide Refuses to Die

Few issues provoke more heat than Nigeria’s North-South dichotomy. Haruna dismisses any fantasy of its disappearance.

Ethnicity, he argues, is not a costume Nigerians can simply remove. Like family, it reproduces itself. Homelands endure. Identities persist. The challenge is not to erase difference but to govern it—through justice, security and economic inclusion.

Nigeria’s failure, in his telling, is not diversity but mismanagement of diversity.

Insecurity: Old Violence, New Megaphones

Haruna rejects the idea that Nigeria was ever truly secure. What has changed, he says, is not violence but visibility.

Tribal wars once ravaged Yorubaland and Hausaland. Colonial conquest itself was born of violence. Terrorism, banditry, insurgency—these are new names for old conflicts amplified by modern communication. Today, a single attack is known worldwide in minutes. In the past, it might surface years later as a footnote in history.

But he goes further, into more uncomfortable territory.

Some of today’s militants, bandits and terrorists, he argues, are products of Nigerian politics itself—migrants allegedly imported to rig elections, mercenaries paid off and abandoned, young men left jobless, armed and angry. When the state creates such forces and then pretends surprise at their violence, it is engaging in self-deception.

Foreign Help or Foreign Debt?

Haruna is deeply sceptical of foreign military intervention. Missiles, airstrikes and counterterrorism assistance, he insists, are never free.

To him, they are investments—down payments on future access to oil, minerals and strategic influence. He points to America’s record: Afghanistan, Russia, endless wars with ambiguous victories. Bombs may be dropped, bodies may fall, but conflicts remain—and bills eventually come due.

True sovereignty, he implies, cannot be outsourced.

Democracy as the Only Way Forward

Despite his harsh realism, Haruna is not cynical. He believes Nigeria has learned something fundamental: coups breed counter-coups, dictatorship breeds stagnation.

Democracy, however imperfect, remains the least destructive option.

As 2027 approaches, he offers no prophecy, only hope—that elections will be credible, that institutions will be empowered, and that insecurity will not suffocate the democratic space.

His advice to the president is strikingly modest: protect the atmosphere. Guard the conditions that allow democracy, however fragile, to breathe.

An Unfinished Reckoning

Sixty years after January 15, 1966, General Ibrahim Haruna’s verdict is sobering. Nigeria’s crisis did not begin with the coup, and it did not end with the Civil War. It lives on—in power struggles, in insecurity, in the uneasy bargain between unity and identity.

The coup was inevitable, he says, because the country that produced it was already at war with itself.

The harder question, left hanging in the air, is whether Nigeria has finally learned how not to repeat it.

● This feature piece is based on an interview conducted with General IBM Haruna, and published in Vanguard newspaper on 15th January, 2026.