By Omotunde Omolehin & Usman Ozovehe

Kogi West is once again counting its dead.

Three worshippers abducted from an Evangelical Church Winning All (ECWA) service in Ayetoro-Kiri, Kabba-Bunu Local Government Area, have died after weeks in captivity, casting a harsh light on the spiralling insecurity that has gripped the district.

Another source cast doubts on the story of the deaths. He told Everyday.ng: “From the information I got. All of them were released. No one died. My cousin’s husband who was one of those running around for thier release told the wife immediately they were released on the 1st of January and she called my mum to inform her thanking God that all of them were found okay in a bush after paying the ransom.”

But the story of their alleged death has also reopened a deeper, more troubling conversation among residents, security observers and civil society groups: the growing belief that illegal mining—allegedly protected by powerful political interests—is fuelling banditry, terrorism and the violent displacement of rural communities.

A church raid and a community in mourning

The victims were among 37 worshippers kidnapped on 14 December 2025 when armed men stormed the ECWA church in Ayetoro-Kiri during a service. After weeks of negotiations, the community reportedly raised about ₦15 million through communal contributions to secure their release.

Only seven people were eventually returned.

“Three of them were already dead on arrival,” the community’s spokesperson, David Ampitan, said in a statement on Saturday. “Four others are currently battling for their lives in critical condition, while about 30 innocent citizens remain in captivity, their fate uncertain.”

For residents of Ayetoro-Kiri and neighbouring villages, the tragedy is part of a grim routine. Bandit attacks, abductions and ransom demands have become frequent, forcing families to sell land, livestock and homes to free loved ones.

Ampitan accused the state government of failing to protect vulnerable communities and alleged that peaceful protests demanding security and rescue operations were met with tear gas and arrests by local authorities.

“Our people are tired of burying loved ones, tired of selling properties to pay ransom, and tired of living in fear while those in authority remain indifferent,” he said, calling for urgent federal intervention.

Beneath the violence, a struggle for minerals

Beyond the immediate horror of kidnappings lies a quieter but equally destructive conflict playing out in the forests and farmlands of Kogi West. The region sits atop significant deposits of gold, lithium and other strategic minerals—resources that should be a blessing, but which many locals now describe as a curse.

One source spelt it out in black and white: “It is no secret that the political class are deeply involved in the ‘Black Market Operations’ called mining.

“From the forests to the cozy offices in government at the Local Government Areas to the main seat of power in Lokoja), issues relating to mining are handled in clandestine manner.

“One of a former governor’s Special Advisers (SA), a quiet one, did much much of the legwork in acquisition of mining sites in Yagba land. They hide under Chinese interests. Currently, that SA is serving under present administration in a higher office

“Some have argued that the mining sites belong to a former First Lady

“Even our people in Okunland are complicit in the whole arrangement. From middlemen to traditional rulers and ‘land owners’.

“It is a long battle that must be fought with sustained media advocacy. Government is neck deep in these activities so they can’t help us. People at home are either too scared to talk or complicit in sale of lands and granting consent letters. Media advocacy is the way out for now. Other non-state actors will join the advocacy when the noise gets louder.”

Interviews with community leaders, security sources and mining experts reveal a recurring allegation: that illegal and quasi-legal mining operations, allegedly linked to influential politicians and foreign partners, are driving insecurity by funding armed groups and forcibly displacing communities.

“The mining sites are not run by our people,” said a community elder from Yagba West, who requested anonymity for fear of reprisals. “Some powerful politicians have proxies. The foreigners have the machines. We have the suffering.”

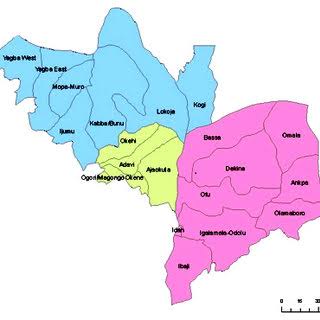

Residents across Yagba East, Yagba West and Kabba-Bunu LGAs describe a similar pattern. Mineral-rich land is identified, acquired through opaque deals or outright deception, and resistance is met with intimidation. Armed men—often arriving on motorcycles at night—threaten, attack or abduct locals. Once fear takes hold and families flee, mining operations expand under heavy security.

“Our fathers were given crumbs for land they thought was useless,” a youth leader in Yagba East said. “Now we see trucks leaving daily with gold and lithium. When we ask questions, we are threatened.”

A familiar national pattern

What is unfolding in Kogi West mirrors developments in other mineral-rich parts of Nigeria. In Niger State, bandit groups have been linked to illegal mining sites, attacking villages and then offering “protection” services to miners. Zamfara State became the most notorious example, where illegal gold mining was so intertwined with armed groups that the federal government imposed a mining ban in 2019 to cut off funding for terrorists.

Katsina and Kaduna have recorded similar complaints: violence first, mining later.

Security analysts describe it as a self-sustaining cycle. Profits from illegal extraction buy weapons and loyalty, which in turn enable further violence and land seizure.

Land grabbing and contested deals

In Kogi West, land disputes linked to mining have become increasingly bitter. One of the most prominent involves Iddo-Ojesa community in Yagba East, where families are locked in a legal battle over a vast expanse of ancestral land now claimed by a mining company.

Community representatives allege that a consent granted in January 2023 for limited exploration was later altered to cover a far larger area—reportedly more than a quarter of the local government—without proper family approval. The speed with which official documentation, including a Certificate of Occupancy, was issued has raised questions among residents about official complicity.

The disputed land reportedly stretches into multiple neighbouring communities, amplifying tensions and fear.

Forgotten villages, targeted violence

Most of the communities hardest hit by bandit attacks are small, agrarian settlements with little government presence—poor roads, no health centres and few security posts. Ironically, many sit atop valuable mineral deposits.

Mining records show that exploration licences in places like Okoloke date back years and have identified not only gold and tantalite, but also lithium, nickel, cobalt and chromium. Yet residents say they have seen no meaningful development, jobs or infrastructure.

Instead, farms are abandoned, forests are occupied by armed groups and young men, stripped of livelihoods, become easy recruits for criminal networks.

A black-market mining economy

Much of the mining activity in Kogi West operates in secrecy. Locals say traditional rulers are sometimes approached by intermediaries who offer cash for consent letters and Community Development Agreements, often without consulting the wider community.

“These agreements are signed, but nobody knows what is inside them,” said a civil society activist in Lokoja. “It is a perfect black-market system.”

Even government interventions have had unintended consequences. When federal mining marshals cleared thousands of illegal miners from a licensed site in Yagba East in 2025, little attention was paid to where the displaced miners went next. Many, residents fear, simply moved deeper into the forests—or into banditry.

‘Life was better before the investors’

For many villagers, the sense of loss is profound. Before the arrival of miners, life was modest but peaceful. Today, roads are destroyed by heavy trucks, water sources are polluted, farms are inaccessible and social life has collapsed under the weight of fear.

“Is it a curse to have minerals in your land?” an elderly farmer in Kabba-Bunu asked quietly.

Environmental damage compounds the human cost. Unregulated pits scar the landscape, forests are stripped bare, and waterways are contaminated with chemicals, threatening long-term survival for those who remain.

Fear, silence and unanswered questions

Perhaps the most striking feature of Kogi West’s crisis is the silence it enforces. Few residents are willing to speak openly. The names of powerful figures are whispered, never recorded. Fear of retaliation hangs over every conversation.

Yet the link between illegal mining and insecurity is becoming harder to ignore. Analysts warn that unless political and corporate networks behind the trade are dismantled—and communities protected and genuinely involved—the violence will persist.

For now, Kogi West’s mineral wealth continues to yield bloodshed rather than prosperity. And as families in Ayetoro-Kiri mourn worshippers taken from a church altar to shallow graves, the question grows louder: how many more lives will be lost before the forest’s secrets are confronted?