By Chinelo Ngolikaego Ezigbo

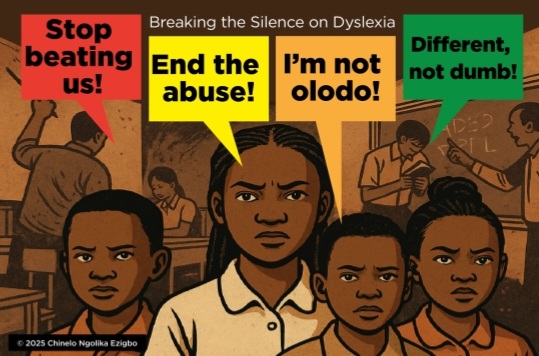

When I first wrote about growing up in Nigeria with undiagnosed dyslexia, the response reminded me I was not alone. Parents worried for their children, adults shared the hidden scars they still carried, and teachers admitted they had never been trained to recognise dyslexia.

My story is not unique. Children today are still being labelled, misunderstood, and punished, while their real needs remain unseen. Yet, unlike when I was a child, Nigeria now has policies that promise every child dignity and inclusion, but those promises are brokendaily.

The Wounds We Don’t See

Children growing up in Nigeria with undiagnosed dyslexia carry a weight they cannot name. As I once did, they live with confusion and humiliation, disciplined in classrooms that mistake their struggle for stupidity, slothfulness, or stubbornness. As a child, I could not find the words to explain what was happening in my own head. I only knew that the letters slipped away from me, and that no matter how hard I tried, my effort was at best taken for carelessness, more often branded as laziness or disrespect.

The adults around me could not make sense of why I was failing where others succeeded. They did not have the knowledge to recognise dyslexia, nor the empathy to look deeper before dismissing me. I remember the names: iti, itiboribo (dullard), olodo (dunce), mumu (fool). They stung more than the cane. I remember the knock on my head as the class erupted in laughter. I remember being dragged to the front during a spelling lesson and flogged, the teacher convinced I was ignoring his instructions. I wasn’t. I was trying my hardest. But I couldn’t make out what he was dictating; the letters would not stay still, no matter how carefully I listened or tried to think them through. That punishment, among many others, still lingers painfully in my memory.

In our society, there is a dangerous belief that flogging or vicious knocks to the head can somehow “open up the brain.” Parents and teachers often misinterpret dyslexia as a child “not having a head for education,” being wilfully lazy, or even spiritually cursed. Some children are taken to prayer houses instead of classrooms, which could give them the right tools and support. These misguided approaches, which rely on violence to compel learning, do not correct anything. They leave lasting damage, wounds no child should ever be forced to carry. I lived this brutal truth.

The bruises faded, but the sense of inadequacy endured. I shouldered the fault, marked by the sting of flogging and the cuts of verbal abuse, and it shadowed me into adulthood. I grew up believing I was not enough, that my failures were a matter of willpower, not wiring. That is the wound dyslexia carves in silence, the wound you cannot see.

It was only much later, after leaving Nigeria, that the silence finally broke. In the UK, I was diagnosed with dyslexia, and for the first time, there was language for what I had lived with.

There were tools and support. And with them I discovered I was never “lazy” or “stupid”; I had always been a bright child with a learning difference no one around me had recognised. That recognition brought freedom. I went on to earn a double degree in Mental Health Nursing and Social Work, but even those achievements could not erase the memory of being humiliated as a child.

Many children in Nigeria are still punished for what they cannot explain, and their scars, like mine, will last long after the cane is put away. Challenging this cultural narrative is as important as changing policy. The silence does not stop with the child. It is written into our schools and policies, leaving children struggling in classrooms with no name for what they are enduring, no training to enable teachers and parents to help. There is just no support for dyslexia.

Silence in Our Systems

The abuses of knocks, flogging, and verbal humiliation persist because our systems remain silent on dyslexia. Nowhere in the Child’s Rights Act, 2003 (CRA), the Universal Basic Education Act, 2004 (UBE Act), the National Policy on Education, 2004 (as revised), the National Policy on Inclusive Education, 2017; Revised 2023 (NPIE), or even the National Mental Health Act, 2021 (NMHA) is dyslexia explicitly named. The absence of that single word has meant weak enforcement, patchy implementation, and no direct safeguards

for children who learn differently.

In July 2024, the National Commission for Persons with Disabilities (NCPWD) issued the National Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) on Inclusion and Access of Persons with Disabilities to Pre-Tertiary Education. These SOPs provide structured tools to prevent misinterpretation and abuse, including enrollment assessments, the development of Individualised Education Plans (IEPs), and clear responsibilities for teachers, school heads, caregivers, and education authorities. The law establishing the NCPWD empowers it not only to create these standards but also to monitor compliance and enforce the Disability Act.

Yet dyslexia is not explicitly named. Without specific recognition in training and accountability systems, even these new SOPs risk being applied unevenly or ignored in practice.

Yet these laws and policies are not empty. The Child’s Rights Act, 2003 (CRA) insists on every child’s right to dignity and protection from abuse. The Universal Basic Education Act, 2004 (UBE Act) guarantees access to basic education. The National Policy on Inclusive Education, 2017; Revised 2023 (NPIE) commits Nigeria to classrooms where no child is left behind. The National Mental Health Act, 2021 (NMHA) protects children with cognitive and learning differences from stigma. And the Disability Act, 2018, makes it unlawful to exclude or mistreat anyone because of a disability or learning difficulty.

The silence on dyslexia does not erase these principles; it challenges us to apply them with courage and clarity. This is the paradox in our systems: silence in the text but impetus in the principle, an impetus we must use to confront the cultural narratives that brand struggling children as lazy, cursed, or less than, and to move towards the strategies that can break this

cycle.

What Needs to Change

The question is not whether we have laws or policies; it is whether we have the will to

interpret and apply them with clarity. I know from my own story that silence is never neutral. It protects the abuser, excuses the system, and leaves the child alone with wounds they cannot explain.

Yet Nigeria is not without protections. Our conventions, laws, and policies already forbid harm, demand inclusion, and call for public awareness. They exist to prevent the very experiences I endured, the shame, confusion, punishment, and stigmatisation that come when learning differences like dyslexia are misread as laziness or a curse.

The mitigation strategies are clear. They fall under three fronts:

1. Prohibiting harm and discrimination.

2. Mandating inclusive education and support.

3. Raising public awareness and accountability.

The challenge is not to invent new principles but to live up to the ones already written, and to apply them directly to children who learn differently.

1. Prohibiting Harm and Discrimination

I grew up in a culture where flogging, name-calling, and humiliation were seen as tools for learning. The scars of that thinking are still with me. Yet the Child’s Rights Act, 2003 (CRA) is clear: no child should ever be subjected to abuse, neglect, or degrading treatment. The African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (ACRWC), 1990, reinforces this duty, insisting that even parental discipline must respect the dignity of the child. The Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act, 2018 (Disability Act) makes it an offence to discriminate, punish, or exclude because of a difference. The National Mental Health Act, 2021, protects children with cognitive and learning conditions from stigma and mistreatment.

The international obligations are no softer. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, 1989 (UNCRC) requires that school discipline be consistent with dignity. The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, 2006 (CRPD), obliges us to remove discrimination and provide equal opportunities. These commitments are not abstract; they speak directly to the knocks on the head, the name-calling, the flogging, and the whispers of curses. Parents and teachers must stop believing that pain “opens the brain.”

Trusted voices across our communities must call out these myths. A child who struggles to read is not lazy, stupid, or cursed; they may simply learn differently.

2. Mandating Inclusive Education and Support

Our laws already promise inclusive education. The Universal Basic Education Act, 2004 (UBE Act) guarantees free and compulsory schooling. The National Policy on Education, 2004 (NPE) and the National Policy on Inclusive Education, 2017; Revised 2023 (NPIE) commit to classrooms where no child is left out. The Disability Act demands that learners are supported in the most appropriate language, mode, and means of communication. At the global level, Nigeria’s ratification of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, 2006 (CRPD), places a clear duty on us to provide accessible, inclusive schools.

The revised 2023 Inclusive Education Policy goes further, naming children who learn differently and requiring continuous teacher training, screening, and tailored support. It mandates assessments to identify learning needs and the creation of Individualised Education Programmes, ensuring that children are not unfairly judged against the wrong yardstick. Extra time, learning aids, and empathetic teaching approaches are not luxuries; they are rights already written into our national frameworks.

And yet dyslexia is still absent from the texts of most policies. That silence has made it too easy to ignore. The framework is there. What is missing is the courage to name dyslexia, to train teachers to recognise it, to use the tools we already have, and to enforce what the law already intends: that every child has a right to learn.

3. Raising Public Awareness and Accountability

Policy on paper will not protect a child who is still beaten and flogged in school. Laws that speak of inclusion mean little if parents are left in confusion and teachers are without tools. Public awareness and enforcement must turn words into practice.

The Disability Act obliges the government to promote awareness of the dignity, rights,

and capabilities of persons with disabilities. The Inclusive Education Policy requires campaigns that reach families in their own languages, faith spaces, and communities, utilising mosques, churches, town criers, and local networks to shift their beliefs. Teachers need training and resources to adapt their methods. Parents need guidance to understand when a child learns differently, so they do not turn to punishment or prayer houses. Communities must see that inclusion is not charity, but justice.

My own story is proof of what is possible. Once I had the right tools and understanding, I discovered I was not “stupid” but simply learned differently. With that recognition, I thrived, earning a double degree and building a career. That same

transformation must be open to every Nigerian child. Our laws and international commitments already give us the authority. What remains is the will to claim it, to reshape our beliefs, to strengthen our policies, and to create the support children with dyslexia need to thrive.

These laws and policies are not empty words. They already prohibit harm, mandate inclusion, and require awareness. What is missing is the step from paper to practice. The courage to use what we have and turn commitments into action.

From Law to Action

The tools are in our hands. What is required is the will to use them. Nigeria is not short of legal frameworks. The Child’s Rights Act, 2003 (CRA) guarantees dignity. The Universal Basic Education Act, 2004 (UBE Act) makes schooling compulsory.

The Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act, 2018 (Disability Act) outlaws exclusion. The National Policy on Inclusive Education, 2017; Revised 2023 (NPIE) promises continuous training and adaptation. The National Mental Health Act, 2021 (NMHA) protects against stigma. And through the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, 1989 (UNCRC), the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, 2006 (CRPD), and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, 1990 (ACRWC), Nigeria has committed itself on the global stage.

The absence of implementation is the challenge. Too many of these protections are silent in practice. Policies sit on paper while children sit in classrooms where knocks, flogging, and ridicule continue.

The Disability Act promises awareness campaigns, yet whole communities remain uninformed. The UBE Act and NPIE require teacher preparation, yet most teachers have never been trained to recognise dyslexia. Even in Oyo, home to the country’s only specialised college for training teachers in special needs, dyslexia is not taught in depth. The curriculum generally covers learning disabilities, but rarely mentions dyslexia or equips teachers with practical tools for early screening and classroom support. As a result, many teachers graduate knowing about inclusion in theory but are still unable to recognise or assist a dyslexic child. Without follow-up in schools or clear guidance for parents, the protections written on paper are not felt in the classroom.

What we lack is implementation. Too often, these protections remain Abuja documents instead of classroom realities.

A PAGE Analysis of the Domestication of the Nigerian Disability Act, 2018 shows how low awareness and a charity-based approach to disability, rather than a rights-based framework, keep children trapped in cycles of shame and punishment.

To break this cycle, action must happen on two fronts:

1. At the community level:

We must tackle harmful cultural narratives. Parents and teachers must drop damaging labels and replace punishment with patience and referral. Faith and traditional leaders should lend their voices, in local languages, to explain that dyslexia is a learning difference, not a curse.

Awareness campaigns must reach rural

areas in the languages families use every day, carried by trusted community voices,

through mosques, churches, town halls, and local media.

2. At the system level:

Laws must be brought to life. Enforcement is critical. The CRA and Disability Act will

remain hollow if they are not implemented. Schools must introduce early screening for learning differences, develop and enforce Individualised Education Programmes (IEPs), and ensure accommodations such as extra time and appropriate learning aids.

Teacher training must be continuous, not occasional. NGOs must be funded to

extend support beyond Lagos and Abuja. Inspection and enforcement should also

check for these practices, not just attendance and timetables. Funding must also reach rural communities where silence is deepest.The step from paper to practice is the difference between silence and support.

Breaking the Silence

I know this because I lived it. I carried the silence for decades, until my diagnosis finally gave me the tools and support I had been denied as a child. In my thirties, after moving to the UK, I was told for the first time that there was a name for what I had struggled with. I was given strategies, accommodations, and encouragement, and I discovered the proof that I was never less. With support, I thrived and earned degrees that once seemed impossible.

Yet across Nigeria, many children are still living the same silence. They sit in classrooms, mocked or flogged for what they cannot explain, while teachers and parents misinterpret dyslexia as laziness or a curse. Countless talented children are pushed aside, labelled, and punished, their potential locked away. Now imagine if they all had the same opportunities I eventually received, in a faraway country where there is no silence, where children are recognised early and supported to thrive.

Every Nigerian child deserves that recognition much earlier in life. Silence must end. Stigma must fall. Neglect must never be allowed again. Nigeria has already signed its promises in law: the Child’s Rights Act, 2003 (CRA), the Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act, 2018 (Disability Act), the National Policy on Inclusive Education, 2017; Revised 2023 (NPIE), and international conventions like the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, 1989 (UNCRC) and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, 2006 (CRPD). Keeping those promises means more than citing them. It requires explicitly naming dyslexia and other unseen disabilities in our laws and policies, and creating dedicated measures for their implementation. Only then will no child who learns differently be left to be broken in the classroom, at home, in a religious place, or anywhere whatsoever.

Breaking the silence is not only about fairness. It is about unlocking the potential of millions of Nigerians.

References:

Nigerian Legislation and Policies

●Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act, 2018.

●National Policy on Inclusive Education (Revised 2023).

●National SOPs on Inclusion and Access of Persons with Disabilities to Pre-Tertiary

Education, NCPWD (July 2024).

●Compulsory, Free Universal Basic Education (UBE) Act, 2004.

●Child’s Rights Act, 2003 (CRA).

●National Mental Health Act, 2021.

●Persons with Disabilities (Accessibility) Regulations, 2023.

Analytical and Governmental Reports

●Adebayo, A. (2025). A PAGE Analysis of the Domestication of the Nigerian Disability

Act 2018.

●Nigeria’s Initial Report on the Implementation of the CRPD, UN Doc. CRPD/C/NGA/1

(24 June 2024).

International Conventions (Ratified by Nigeria)

●African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (1990).

●UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989).

●UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2006).

■ Ngolikaego Ezigbo is a mental health nurse and social worker with the NHS (UK), and a former disability analyst. She is passionate about neurodiversity, inclusion, and improving support for children with learning differences in Nigeria and beyond.